Author: Ben Greenwood

Posted: 07 Apr 2020

Estimated time to read: 5 mins

In a world full of 24 hour news and with unlimited access to the internet, the latest stories from around the world are never far away. Whilst these stories connect us, and it’s good to keep up to date - it’s also important to be mindful of what we are consuming.

Just as we eat healthy food to nourish our bodies, ensuring we consume information that is of a high quality will help to sustain our minds. But how do we ensure that we, and our students and children, are equipped to navigate the vast network of information that is the internet?

Over the last decade we’ve seen terms like ‘fake news’ and ‘post-truth’ entered into the Oxford English dictionary. They are terms that are a dystopian but necessary way of describing the internet in the 21st century.

Figures from Ofcom show that 41% of children aged 12-15 believe that the news they read on social media is trustworthy all or most of the time, whilst 30% believe that if a website appears on a search engine results page, it must be reliable.

Teachers and parents both play a crucial role in teaching media literacy amongst our young people. By giving young people the tools they need to navigate this world of information, we help them to better inform themselves and sort the reliable sources from the fake news and sensationalism that lay astrew their Facebook timelines.

What is Media Literacy and Why is it Important?

To be media literate is to properly engage carefully in our digital society. For students this usually means developing an understanding of a topic using online sources - then using critical thinking skills to thoroughly assess whether the information they have learned is from a reliable source and is true before they consolidate that knowledge.

But media literacy goes further than this, it also relates to how we create messages, how we access and experience information and how we analyse and organise it. Being able to use the internet properly and sort the nuggets of reliable information from the fake news chaf, and dealing with fake news in a timely and responsible way.

As we find ourselves in a period of uncertainty, with students using the internet unsupervised and beyond the reach of school content blockers, how can we ensure that they are prepared? Not just for the immediate future, but for the continuing fight for truth online?

How Can Students Become More Media Literate at Home?

It’s more important than ever for students to recognise the importance of their digital lives. With more time at home and raised panic levels giving credence to stories like the coronavirus 5G conspiracy theory, we need to teach students to think for themselves and wade through the low quality information out there to find valuable educational material.

Finding reliable information online

The first hurdle in the search for reliable information comes less than a second after clicking the search button or opening a social media app - choosing the information they interact with.

Social media users in particular have a unique relationship with information. It is randomly showered upon them rather than shown as the result of a specific search query. The article in question could be written by anyone or any organisation.

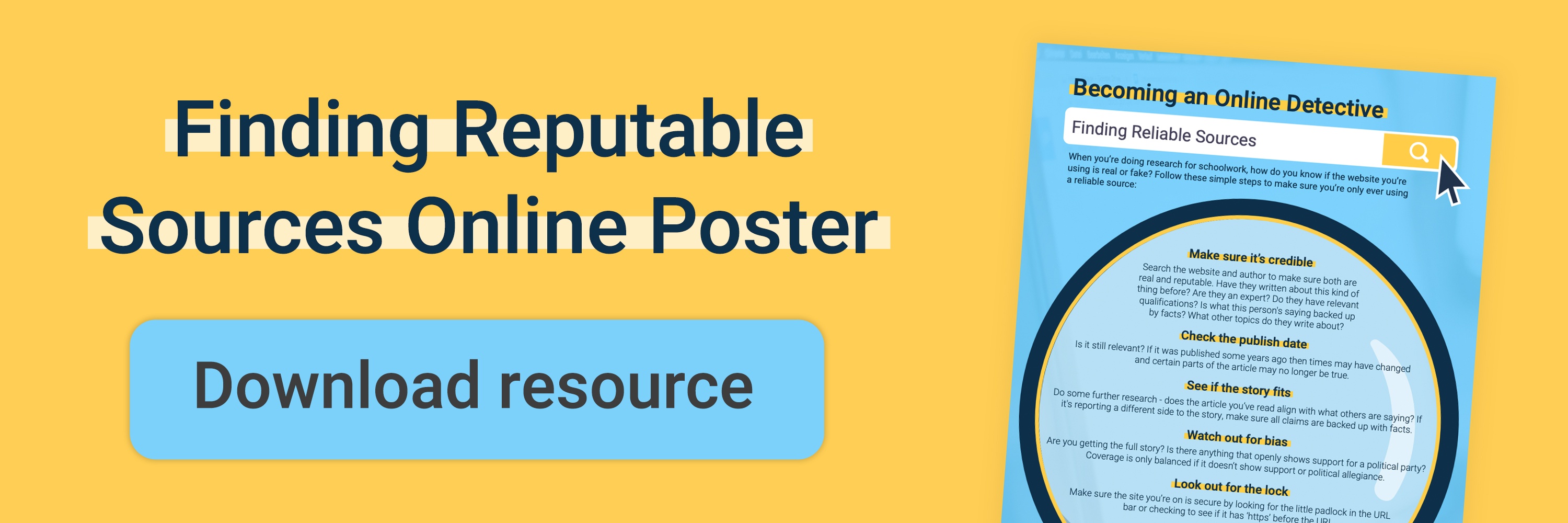

The first step here is to look at the URL and title of the link or search result. Does the website name match the actual title? Some fake sites use the names of well-trusted sites like BBC or Financial Times and are designed to look just like the real thing. The biggest giveaway for these sites is the URL. If it doesn’t match the official site’s URL, you’re on a dodgy site.

Once you’re happy that the site is legitimate, run a quick google search of the author. Are they established in the field you’re researching? This can also be done with social media accounts that have shared a story. If someone is an expert, it's more likely that they’ll share well researched information. Look at some of their post/writing history and assess their reputation before using the article.

If the article makes a claim, e.g “most teenagers have Iphones rather than other brands”, it must be backed up by a study or questionnaire results. You should also research around this to see if this is really the case. Read other articles and papers to see if the background research returns a consensus, and whether it’s the same as the article you’re reading.

Finally, make sure the article is up to date. If it was written a number of years ago, the data that was used to write it has likely changed and it will no longer be accurate. Always check the publish date to see if there are any updates that have been added to the article to bring it up to date.

Reacting to fake news

Ofcom’s report revealed that 4 in 10 teens said they would not do anything, or ignore it, if they saw fake news online. This leaves false information free to continue circulating after around 40% of teenagers have seen it.

If you find a site or article that you believe to be fake news, it’s important that it is reported so the relevant authorities can deal with it and it can be removed from circulation - but what should students do if they see what they believe to be inaccurate or false information?

If the article in question is shared via social media, then there will be a report or flag button in the post’s options. You should report the article and give details as to why you believe it to be misleading so the platform can investigate the user.

As for websites that you believe to be fake, leave google feedback to warn other users and flag the site to google so it can be processed. This may lead to the site’s removal, saving other users from falling into a fake news trap.

Being a responsible online citizen

A continuous approach we can take to stopping fake news, is to stop sharing articles on our own social media pages without reading them thoroughly. Headlines are designed to compete for attention on colourful and persuasive timelines, and even the most reliable sources on the internet can be found guilty of clickbait.

If you read a headline that sounds extreme, read the article before you like, comment or share it. The story itself may be different to what the headline suggests. Refrain from sharing misleading headlines and, if you’re feeling up for a bit of social justice, leave a comment underneath warning others that it is misleading.

By working in unison, we can help to stop the spread of false information and fake news - something that becomes more dangerous the more stress and panic grows. But by teaching our students to do that same, we might be able to stop the social media timelines of the future from constant flooding of post-truth content and panic invoking false headlines.